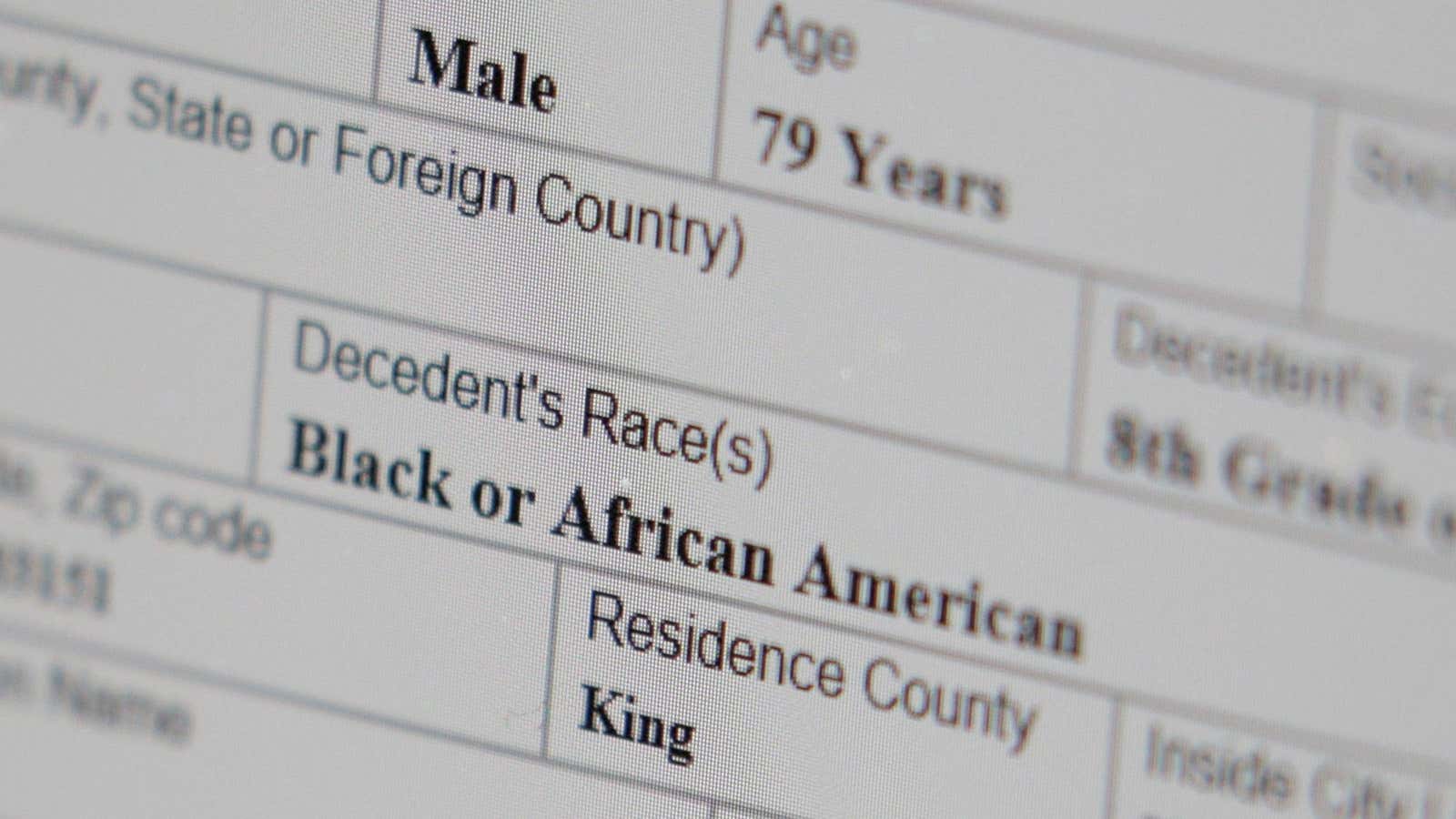

Black Americans in certain age groups are as much as nine times more likely to die of Covid-19 than similarly aged whites, and overall their fatality rate is nearly four times that of whites, according to new data from Harvard’s Center for Population and Development studies.

Months into the Covid-19 outbreak, there are still many things scientists don’t know about how the disease hits, so it is hard establish all the reasons for such discrepancy between races. One of many factors they are beginning to understand, however, is the role pre-existing conditions play in patients with severe, and even fatal, cases of the infection.

Studies of hospitalized cases of Covid-19 indicates that the most frequent condition also found in Covid-19 patients is hypertension, or persistent high blood pressure. A study conducted of 1,590 patients in China found nearly 17% of patients had hypertension, and a smaller study found hypertension in 58% in patients hospitalized in Wuhan. A similar US study looked at 5,700 hospitalized patients in New York City: The majority of them, nearly 57%, had hypertension. This is higher than the average occurrence of hypertension in the US (45% of the population), suggesting that people with hypertension are at higher risks of severe Covid-19 infection.

In the US, hypertension is a chronic condition that disproportionately affects the African-American population. According to 2017 data from the American College of Cardiology, 57.3% of (non-Hispanic) Black adults suffer from it, compared to 46.5% (non-Hispanic) white adults.

Systems of oppression

The increased rates of hypertension in Black Americans can’t simply be pinned on genetics. Some may have a genetic predisposition to hypertension, as any of us do, and genetic risks may be higher in people with African ancestry.

But chronic diseases are influenced by factors beyond genetics, including diet, access to preventive health, and certain behaviors, such as smoking. These factors are, in turn, are often linked to socioeconomic factors, including race. One of the consequences of racism is that, on average, African Americans have fewer resources and worse socioeconomic circumstances than whites. But that is not the whole story.

Racism on its own increases the likelihood of developing hypertension. Stress is a known cause of hypertension, and racism and discrimination have a well-established link with stress (pdf, p. 30).

While there aren’t studies that quantify how much hypertension can be attributed directly to the experience of racism—because it is hard to extrapolate the relative impact of racism per se from other connected socio-economic issues—University of Florida anthropologist Clarence Gravlee found specific links between high blood pressure and racial discrimination, independent from the impact of worse socioeconomic circumstances or genetic ancestry.

Gravlee, who studies the effects of racism on health, based his 2005 study in Puerto Rico where, he explained, people of African ancestry are broadly perceived as belonging to two different groups, depending on some physical and social features. Lighter skin, as well as other traits such as hair texture, mark people who are considered trigueños (an intermediate group, in-between black and white) as different from Blacks. The former experience less racism and better social acceptance than the latter.

The study looked at 100 people, randomly selected from households in neighborhoods of different socio-economic background, and recorded their blood pressure as well as their skin pigmentation.

“For people who were assigned to the relatively privileged category, as their income and their education went up, their blood pressure came down,” Gravlee said of his Puerto Rico research, “but for people who were defined as Black, their blood pressure actually went up along with their income and education.”

Similar patterns have been found among African-Americans in the US, suggesting the health impacts of dealing with racism don’t go away because of an improved socio-economic situation. On the contrary, for those who are more likely to experience and perceive higher levels of discrimination, an improvement in socio-economic status is often associated with moving in historically white-dominated contexts, leading to even more frequent instances of perceived discrimination.

“What we showed is genes don’t matter, skin tone doesn’t matter [in relation hypertension], what matters is how people see themselves and how they are defined by others,” Gravlee said.

Exposure to racism doesn’t just raise blood pressure temporarily, in response to single incidents; it causes chronic, diagnosable hypertension. “Earlier research had provided indication that discrimination increased blood pressure reactivity to stress,” said Elizabeth Brondolo, a professor of psychology at St. John’s University who has researched the psychophysiology of discrimination for decades. But more recent research, she said, found the link could be established even with diagnosable, chronic hypertension, not simply with temporary occurrences of higher blood pressure following a stressful event. “We saw a fairly consistent relationship between the individual level of discrimination […] and the value of ambulatory blood pressure.”

The weathering hypothesis

The impact of racist treatment and discrimination is profound, and permanent: It literally wears down the body. Research published in May 2020 in the American Journal of Human Biology found African Americans living in Tallahassee, Florida, who reported higher levels of racial discrimination had shorter telomeres than those who reported less discrimination. Telomeres are the caps on the ends of our chromosomes, and they naturally shorten as we age. But high levels of stress can shorten telomeres quicker than normal, indicating they are effectively aging faster. “The stress of dealing with racism exerts wear and tear on the body and speeds up the aging process,” Gravlee said.

This concept, known as “weathering,” was first introduced in 1992 as a hypothesis by public health professor Arline Geronimus, and has since found much empiric evidence in support, including the study on telomeres. The idea of weathering, Gravlee says, is also consistent with recent findings showing that African Americans experience coronavirus death rates higher than white people who are over a decade older than them.

The stress of racial trauma doesn’t need to be protracted through life to be significant, either: There is evidence showing that it impacts development in utero, showing in birth outcomes, too.

Diane Lauderdale, a public health science professor at the University of Chicago, looked at the birth outcomes of pregnant women who were perceived to be Arab in California in the months following the terror attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, when the Arab community experienced increased racism and discrimination. She found they were 34% more likely give birth to an infant with a low birth weight than they were a year prior.

Low birth weight, in turn, is a predictor of hypertension later in life, and while there haven’t been similar quantifications of the increased risk brought on by discrimination for African American mothers, studies have found racism is an independent factor increasing their likelihood of preterm delivery and low birthweight.

Yet another reason for the prevalence of hypertension could be the epigenetic activation caused by exposure to the stressors of racism. Although the sequence of an individual’s DNA is determined at birth, the expression of the genes in that sequence can be determined by external factors. So, for example, a person with a certain genetic makeup might develop hypertension in response to certain environmental stresses—or might not, if those stresses are absent. This doesn’t mean that there is an inherent genetic difference, but merely a difference in the reaction of the same genes.

While stress has been linked to epigenetic modification, research on how exactly the stress of racism activates epigenetic modifications that increase hypertension risk is still underway. “It makes sense that the kinds of experiences and exposures we have would also change the way genes are expressed and our bodies operate,” Gravlee said.

But he also worries there is a risk of focusing too much the biological reasons why racism contributes to certain health issues—whether by weathering, epigenetically, or inter-generationally—while the important conclusion is simply that it does. “It’s very clear that social environment that could be altered by policy are the root cause of racial inequalities in health, and we don’t actually need to wait to understand all the biological mechanism to start changing the problem,” he said.