The UK’s new support strategy for its homegrown semiconductor industry has surprised those who had been waiting almost two years with its unambitious nature. Prime minister Rishi Sunak said on Friday that his government will allocate £1 billion ($1.24 billion) to the industry’s development in the country over the next decade, with £200 million of that sum to be rolled out between now and 2025.

Some critics and investors pointed out that the sum pales in comparison to the US’s CHIPS Act, announced last year, which pledged $52 billion to the industry for ramping up domestic manufacture of semiconductors. In April, the European Union announced a $47 billion semiconductor support program. Even TSMC alone—as the biggest semiconductor manufacturer, turning out more than half the world’s supply—outpaces the announced quantum of British investment. TSMC’s operating expenses for the year ending March 31, 2023 were $36.8 billion, or about $1.24 billion (£1 billion) every 12.5 days.

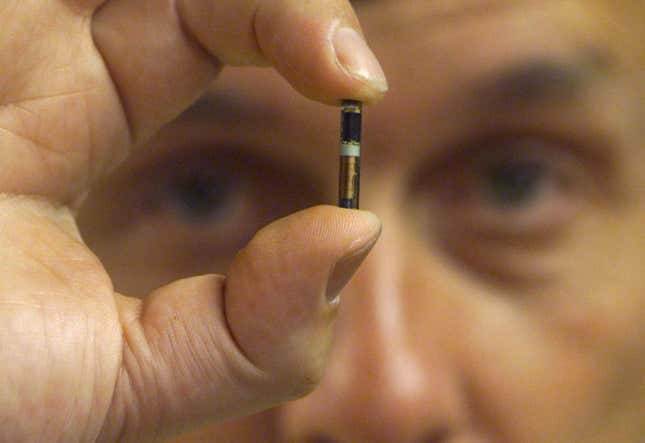

Countries are still trying to deal with global shortages of semiconductors

Twin fears have propelled the US and EU to invest heavily in new chip manufacturing capacity. Covid 19 saw global supply chains of all kinds of products grind to a halt, and chips have been in short supply during and after the pandemic. Semiconductors are now so essential—used in everything from phones and laptops to bank ATMs, trains, medical technologies, and the operation of internet itself—that no country can afford to be without them for long.

Secondly, tensions have been mounting between Taiwan, the base for TSMC and other semiconductor foundries, and China. Taiwan is the biggest manufacturer of chips in the world, and any aggressive moves by China towards the island nation could potentially make a huge dent in supply. Citing this very reason, in fact, Warren Buffett sold off a $4.1 billion stake in TSMC over the past six months.

The UK’s strengths in the semiconductor industry have, thus far, been evident more in design than in manufacturing. Arm, a Cambridge-based chip designer, for instance, licenses its work to chips used in around 95% of the smartphones in the world. (Softbank, which owns three-quarters of Arm, has been preparing to take the company public.) The lack of a robust domestic chip supply, however, is proving to be an industrial deficiency. In February, the Cardiff-based IQE, which manufactures components of semiconductors, warned that it may be forced to move to the US or Europe, “where the money is,” if the UK’s strategy wasn’t best for its business.

In a release, the UK said it is not trying to compete on chip manufacturing, but rather that its plan “will focus on growing the UK’s unique and already world-leading strengths in compound semiconductors, research and development, intellectual property and design.” Compound semiconductors are manufactured from two or more elements, as compared to the more common kind of semiconductor, which is made out of just silicon.

In the same government release, Sean Redmond, a managing partner at Silicon Catalyst, an accelerator focused on chips, said: “These well thought through policy interventions will help UK companies drink from the global fire hydrant of opportunity as this critically important industry grows to $1 trillion by 2030.”

But others were less impressed. Simon Thomas, chief executive of Cambridgeshire electronics company Paragraf, told Politico the UK’s strategy was“flaccid.” Amelia Armour, a partner at Amadeus Capital Partners, which invests in semiconductor businesses, told the Financial Times that the £1 billion amount was “disappointing.”